7. In addition to living in Tokyo, you have traveled the world and have lived in numerous places - New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Geneva, Paris and others. After reading your book, it’s obvious Tokyo is your favorite city. What are other places you really like and (if you wish to tell) what would be your least desirable place?

Paris. Vienna. Stockholm in the summer. Hawaii in the winter. I think Dhaka would be at the bottom of the list. Karachi would be a close second from the bottom.

8. After the publication of Tokyo Junkie, do you have any other projects you are planning?

I’m going to update and revise Tokyo Outsiders, a sequel to Tokyo Underworld which I did in Japanese in 2002, consisting mostly of material I had to cut out of Underworld. I was waiting for the film/TV series version of Underworld to come out before doing an English version but it never materialized after over 5 different studios had considered it. So, that’s my next move - and hopefully it will come out with the TV series that Terence Winter and Sherry Marsh are doing of TU for Legendary Global. There is a lot of new material to organize.

9. You first came to Tokyo in the US military at 19 years old. What would you recommend 19-year-olds reading this today do with their lives?

Have as many diverse experiences as you can and don’t worry so much about what you’re ultimately going to do with your life. That will eventually sort itself out. James Michener said he thought most people could wait until the age of 40 before deciding on a career path—with the exception maybe of someone who wants to become a doctor, which takes 8-10 years.

10. Is there anything else you would like to say – about Tokyo, yourself, the world or the meaning of life?

I have some advice on how to live. Try to excel at at least one thing. Try to do some good for your fellow man. Remember the Aristotle maxim: "Happiness is the pursuit of excellence in a worthwhile goal." Also keep in mind the famous quote from the samurai Miyamoto Musashi: “Do not regret what you have done. There is more than one path to the top of the mountain.”

[1] General Headquarters for SCAP (Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers - General Douglas MacArthur).

[2] Kyojin No Hoshi (巨人の星 in Japanese - translated into English as “Star of the Giants”) is a character in a Japanese anime of the same name. Read Tokyo Junkie for details about the fascinating story of his life and that of his family.

Tokyo Junkie will be published by Stone Bridge Press on 20 April 2021.

For a previous (and much longer) interview with Robert Whiting that Don MacLaren did for Wilderness House Literary Review, please click here.

For a previous (and much longer) interview with Robert Whiting that Don MacLaren did for Wilderness House Literary Review, please click here.

© 2021 by Don MacLaren

For permission requests, please contact Don MacLaren: info@donmaclaren.com

(On some devices there may be issues with photos covering text on this webpage. For review and interview without photos, click here.)

Review of Robert Whiting’s Tokyo Junkie: 60 Years of Bright Lights and Back Alleys...and Baseball - followed by interview with the author

By Don MacLaren

2 April 2021

In the early 1960s, Japan was a poor country still emerging from the ravages of World War II. Pollution was a terrible problem. Most people in Tokyo didn’t have flush toilets. Yet Robert Whiting found himself fascinated by the city when he arrived there as a 19-year-old GI in 1962. His fascination has continued unabated since then, as evidenced by his latest book, Tokyo Junkie: 60 Years of Bright Lights and Back Alleys...and Baseball.

“I was as naïve as they come,” Whiting writes of his life before Tokyo. But his naivete didn’t last long as he sought out new experiences while working hard at learning Japanese. Whiting often ventured out from Fuchu Air Station, on the outskirts of Tokyo, where he worked in US Air Force Intelligence, to places like Shibuya, Ginza, and Shinjuku, where he encountered yakuza, bargirls, Catholic priests, doctors, haiku-writing bohemians and others. And though he was surrounded by numerous vices that he could have become addicted to, it was Japanese baseball that he became obsessed with.

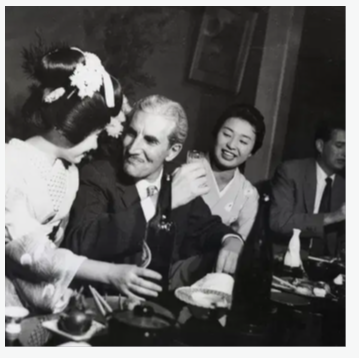

Ginza nightlife, 1960s (From Robert Whiting collection)

The 1964 Olympics brought Japan to the eyes of the world – and brought tears of pride and joy to the eyes of many Japanese. Whiting writes that he “…watched fascinated, astonished, as, before my eyes, the city evolved, in a few short years, from a fetid, disease-ridden third-world backwater into a modern megalopolis in what many believe to be the greatest urban transformation in history.”

Though many Japanese were moved to tears because of how far they had come since 1945, there were also tears of grief and shame during the Olympics, when the Dutch judo contestant Anton Geesink won the Gold Medal against the Japanese Akio Kaminaga in the Open category. (The Japanese had requested that the Olympic committee include judo in the games.)

Whiting writes about how Geesink’s win revealed the strong mixed and complicated feelings that the Japanese harbored toward foreigners. Sometimes, Whiting shows us, those feelings were not mixed at all, but outright hostile. Despite his criticisms though, it is clear that Whiting’s love for the country, and especially Tokyo, is much stronger than any other feeling he has – mixed or otherwise.

Whiting does not confine his criticism to the Japanese. Americans in Japan could be as narrow-minded as any Japanese, he tells us. When Whiting’s enlistment ended in the mid-'60s and he decided to stay in Japan, many of his fellow GIs accused him of being a “Jap-lover.”

Whiting has spent most of his life since leaving the Air Force in Tokyo. In the decades since the ’64 Olympics, the city has gone through another miraculous transformation. Whiting’s own experiences in those years have been just as fascinating.

In 2013, Tokyo was again awarded the Summer Olympics. By that time it had become the city with the highest GDP in the world, with more Fortune 500 companies than any other metropolis. And the world had become enamored with Japanese culture; people had become hooked on everything from sushi to anime. Japan by then had also stumbled through numerous corruption scandals, and its economy had shrunk during the “lost decade” of the 1990s. By 2013 Whiting had graduated from a Japanese university, mastered the Japanese language, written numerous critically-acclaimed books (including the Pulitzer Prize entry, You Gotta Have Wa), been honored by US presidents and received death threats from yakuza after writing Tokyo Underworld: The Fast Times and Hard Life of an American Gangster in Japan. And he had married a Japanese woman – Machiko Kondo – who made a career as an officer for the United Nations.

Whiting takes us on a delightful tour through all of this.

Tokyo Junkie brings to mind two other fine books that I’d highly recommend reading after you've finished Tokyo Junkie. One of them is the Pulitzer Prize-winning A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam by Neil Sheehan, which traces America’s role in Vietnam up to the 1970s and on a parallel level the life of John Paul Vann, an American who spent many years in war-torn Vietnam and died there when his helicopter hit trees while flying at night.

The other book is Whiting’s own Tokyo Underworld, which traces Japanese-American postwar relations, and on a parallel level the life of Nick Zapetti, a former US Marine, who came to Japan during the postwar Occupation and stayed there. Zapetti would boast that he was the richest American in Japan, but he lost most of his money and died in his adopted country a broken man.

Sheehan and Whiting skillfully interweave the lives of the main characters (and in the case of Tokyo Junkie, the narrator) with larger forces. This makes the books very personal stories as well as macro-political/economic narratives about places that have had an immense impact on the United States and the rest of the world.

Tokyo Junkie is different from the two other books, however, in that both Vann and Zapetti were dark and conflicted figures. Whiting has lived through a great deal of drama in his years in Tokyo, but reading Tokyo Junkie it’s clear that his own dramatic story is a happier one.

By the time Zapetti died he had planned to kill all those he disliked. It seems, however, he disliked himself more than anyone else. As Whiting writes in Tokyo Underworld, Zapetti told him shortly before he died that “…any man who left his own country to live in another was an ‘asshole,’ deserving of everything bad that happened to him.”

Zapetti was wrong. Whether it is in Tokyo, or anywhere else in the world, one will find heroes, villains and fools. Zapetti belonged in one - or both - of the latter categories. By living and writing Tokyo Junkie, Whiting deserves to be listed in the first category.

If you have any interest in learning of how a fascinating city and a fine human being have developed over the course of nearly 60 years – with many trials, tribulations, joys and successes - read Tokyo Junkie!

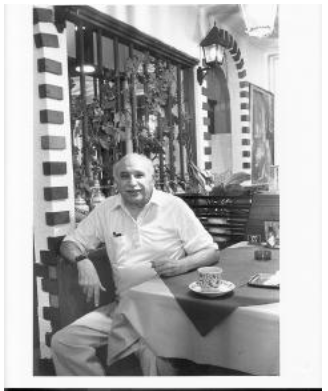

Nick Zappetti, Tokyo, early 1990s, shortly before he died (Greg Davis)

Interview with Robert Whiting, author of the memoir Tokyo Junkie

© 2021, Don MacLaren and Robert Whiting

By Don MacLaren

2 April 2021

1. Why did you write Tokyo Junkie?

This book started with a 25,000 word five-part series on the 1964 Tokyo Olympics I did for The Japan Times which got a lot of attention. I wanted to expand it into a book but my agent told me no one wants to read a book about any Olympics. Then my Japanese publisher Kadokawa came along and asked me to turn it into a memoir, comparing the city’s growth set against my own personal growth over the decades. A tale of transformation so to speak. I submitted a 175,000-word draft, which Kadokawa published as is. I then cut it in half for the US market while adding 20,000 new words worth of material.

2. Why did you choose this title?

Because I’m addicted to the city. I can’t seem to stay away from it. The energy of the place just sucks you in.

3. Is there anything you regret not having put in the book?

Yes, I had to cut a lot of stuff. I had a lot of material about Yutaka Enatsu, the famous pitcher who went to prison—whom I knew personally. An essay about an evening at Shigeo Nagashima’s house, another about a visit to Sadaharu Oh’s home. Long, long interviews I did with Hawaiian sumo wrestlers Takamiyama and Konishiki and turned into a book in Japanese. Six hours-worth of taped interviews with professional wrestler The Destroyer, who was an icon in Japan. 10,000 words about the postwar era Black Ops group in Tokyo, the Canon Agency—I’d met and interviewed a couple of agents who were still alive (one still is today). They were involved in kidnapping communist agitators and fighting with North Korean infiltrators, who were trying to flood Occupation-era Japan with heroin and crystal meth. Then there was the illicit romance between Charles Kades (a high-ranking GHQ [1] official during the Occupation) and the Viscountess Torio, a member of the Imperial family, which adversely impacted GHQ policy. My experience working for the CIA on top secret U-2 spy missions. Surviving the Cuban Missile crisis in Tokyo when we all thought we might die. The entire Hollywood saga—Nick Pileggi, Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader and others involved in long and numerous attempts to turn Tokyo Underworld into a movie or TV series. There was a lot of material I wanted to use, but these days it’s hard to sell a book in the USA that’s longer than 100,000 words. So, I had to cut everything out that wasn’t directly apropos to the main thesis, which was the growth and transformation of the city of Tokyo set against my own personal growth and transformation over half a century. The book is more focused now, but I cut enough out for another book entirely.

4. The book traces your life in Tokyo since 1962, but also traces Tokyo’s amazing changes – good and bad – since then. If there were one thing you could alter about Tokyo’s changes and one thing you could alter about your personal changes since 1962, what would you choose?

I enrolled in a Master’s degree program at Sophia University in Tokyo thinking that maybe I would get a PhD somewhere eventually, but then dropped out when I was offered a good paying job at Encyclopedia Britannica. With hindsight I realized that enrolling in a post-graduate course was a mistake in the first place. Academia wasn’t for me. I’ve come to discover over time that being a non-fiction author/journalist is a much more rewarding career. You touch more people. And you have more interesting experiences. One more thing, I smoked for 14 years. Hi-Lite cigarettes. Bad habit. I also drank too much, but let’s not get carried away here.

As for Tokyo, I think it was a mistake to adopt the Courbusier style of high-rise glass and steel (or concrete) box-like apartments. They are awfully impersonal. They ruined neighborhood life. I like Kengo Kuma’s naturalistic approach.

5. The 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics was cancelled due to COVID-19. It has been rescheduled for summer 2021. Was it a good idea to reschedule the Olympics for 2021 when COVID-19 is still a crisis? How would you have handled the rescheduling if you were responsible for it – or would you have cancelled the Olympics, or not rescheduled them at all?

I would have probably done the same thing. It was entirely reasonable to expect that the virus would be gone by summer 2021. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said IOC (International Olympic Committee) chairman Thomas Bach offered to move the Games back to 2022. Abe said no. I wonder what he would say now. What I think was a mistake—one made by the IOC—was to move the marathon to Hokkaido to escape the Tokyo summer heat. There is a marathon course in Hakone. Perfectly acceptable. It’s in the Kanto Plain, much closer to Tokyo. The IOC unilaterally made the switch to Sapporo without consulting the Japanese government. I have a hard time understanding that.

6. There are numerous influential people – in both good and bad ways, famous and infamous – in Tokyo Junkie who you have known. If you had to pick those who have had the greatest influence on you, who would you pick - and are there any you wish you’d never known?

The character Dwight, the one who pushed me to write The Chrysanthemum and the Bat while we were both living in New York City. I never would have attempted it if he hadn’t goaded me into doing it. Doing that book enabled me to start a career as a writer and become proficient in my craft after putting in the obligatory 10,000 hours, as Malcolm Gladwell puts it. That in turn enabled me to do You Gotta Have Wa which was a vastly superior book and prepared me to do a complex and difficult undertaking like Tokyo Underworld.

Tsuneo Watanabe helped turn The Chrysanthemum and the Bat in Japanese into a best seller. David Halberstam had a big influence on me, introducing me to my agent and other movers and shakers in New York City. Sadaharu Oh showed me what hard work really is and what the meaning of dignity is. Kyojin No Hoshi. [2]

Most important of all was my wife, Machiko Kondo. She became a great anchor.

I wish I never met Yamamoto, the slobbery thug, yakuza actually, who handled security for Riki Mansion. I could have done without knowing him.

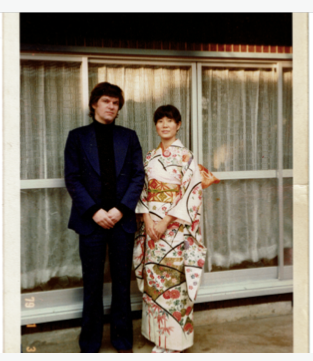

Robert Whiting and Machiko Kondo, 1979 (From Robert Whiting collection)

Robert Whiting (left) and Don MacLaren, Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan, Tokyo, February 2016 (Don MacLaren)

You can learn more about Don MacLaren at donmaclaren.com.